Country Sports - SANDRA SCHWAB | Historical Romance Author

Main menu:

- Welcome

-

Bookshelf

- Eagle's Honor

- Allan's Miscellany

- A Love for Every Season

- Stand-alone Novels

- About Sandra

- Research

- Author Services

- Contact

- Blog

Country Sports

"When you have killed all your own birds, Mr Bingley, I beg you will come here,

and shoot as many as you please, on Mr Bennet's manor. I am sure he will be

vastly happy to oblige you, and will save all the best of the covies for you."

(from Pride & Prejudice by Jane Austen)

Towards the end of the 18th century, nature was increasingly seen as a positive force, and consequently, country life and country pursuits gained new popularity with the upper classes. Country sports such as hunting, shooting, and fishing, were now regarded not merely as pleasant male activities, but as virtuous and prestigious. Indeed, in the course of the following decades, the upgrading of country sports resulted in such an ideological shift that by the beginning of the Victorian Age (1837), they were regarded as "typically British" and were linked to ideals of masculinity and the ideology of Empire. In 1859 one journalist argued that field sports "are as essentially necessary for the maintenance of our national character as sleep is to our existence. [...] There is a bold and manly character in connection with this sport which is highly in unison with the character of an Englishman" (New Sporting Magazine 228, December 1859).

Traditional and new prey:

deer: overhunted and thus became extremely scare in the wild by the late 17th century; deer parks on aristocratic country estates were for show rather than sport

partridges and pheasants: became the substitutes for deer; by the early 18th century they were shot with the newly improved muzzle-loading flintlock guns (rather than caught with nets)

hares: another deer-substitute; hares were not just shot, but in hare coursing they were also pursued by specially trained greyhounds (the winner was the dog which killed the hare)

fox: fox hunting became popular in the 18th century and was then also formalised (costumes, manner of pursuit, entertainments after the hunt); foxes were hunted on horseback and with a pack of dogs. Typically, both the horses and the dogs were specially trained and bred for the business of the hunt.

Shooting vs Hunting:

Shooting refers to walking up game (birds or hares) with dogs, while hunting means the pursuit on horseback of animals such as foxes.

Sports:

Until the 1850s the word sports referred to field sports, that is, hunting and shooting.

The enclosures of the late 18th century not only made for more profitable farming, but well-drained fields separated by jumpable hedges or dry walls also made for a livelier hunting ground. Fox hunting and agricultural improvement thus went hand in hand.

Sporting Magazines

Since the late 18th century sporting pictures and portraits of country house owners in sporting dress became increasingly popular. An early monthly sporting magazine was founded in 1792: Sporting Magazine, or Monthly Calendar of the Transactions of the Turf, the Chase &c. (1792-1870; price: varied between 1s and 2s 6d.). Other such magazines followed in the course of the 19th century, e.g.

Sporting Review, A Monthly Chronicle of the Turf, the Chase, and Rural Sports in all their Varieties (1839-70): devoted to racing and field sports

New Sporting Magazine (1831-70): a monthly, founded by the journalist and writer Robert Smith Surtees, the publisher Rudolph Ackermann, and the sporting journalist C.J. Apperley (aka Nimrod)

Field (1853- ): began as the Field, or Country Gentleman's Newspaper, a weekly (published on Sundays), price 6d, covered hunting, shooting and related sports

Sporting Gazette (1862-79) / Country Gentleman (1880-1915): a London-based weekly, price 3d (4d since 1864; 6d since 1880), covered the turf, steeple-chasing, coursing, hunting, cricket, shooting, fishing, aquatics, chess and archery; early target audience: upper-class men; in 1879 the title was changed to Sporting Gazette and Agricultural Journal, one year later to Country Gentleman, Sporting Gazette and Agricultural Journal: A Newspaper for Country Families

Other Victorian sporting magazines covered horse racing (e.g., Sporting Chronicle, 1871-1983, target audience: lower middle classes) or athletics, billiards, boxing, football, golf (e.g., Sporting Life, 1859-1998)

The Game Laws

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, country sports were the province of rural communities, in particular of the landed classes, who fiercely protected their privileges.

Shooting in particular was indicative of social status and wealth: shooting birds and hares was a special privilege of the landed class and a result of the so-called game laws, which had been first introduced in Norman times and were still in place in the Victorian age. They restricted the shooting of game to landlords and forbade the public selling of game. A revision of the law in 1831 had introduced a licensing system that allowed for the purchase of a license to shoot on somebody's land. However, those who would have dearly needed the hares and birds were still excluded: the poor rural workers, whose situation had gradually worsened in the decades before until they were practically starving in the 1840s. Thus, the game laws produced great tensions in rural communities as poaching was met with drastic punishments on the one hand, and many gamekeepers were brutally murdered, on the other.

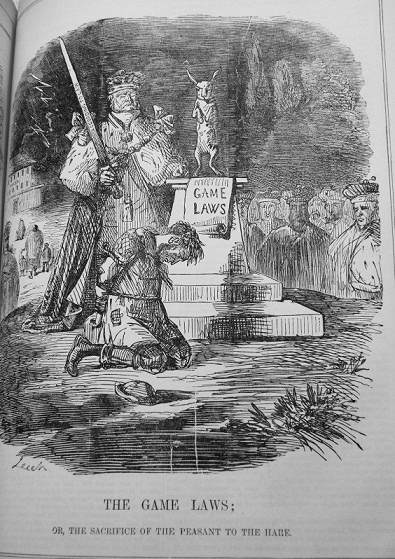

In the minds of middle-class writers, blood-sports became therefore connected to idleness and, in the case of politicians, incompetence. The game laws were fiercely criticized (see "The Game Laws" by John Leech, from Punch), and many concluded that a reconcilliation of the rich and the poor in the countryside could be effected only by an abolition of the game laws.

In addition, addition, country sports were sometimes condemned as cruelty to animals. In the mid-19th century, the criticism focussed primarily on Queen Victoria's German husband, Prince Albert. He had become infamous for his enjoyment of the mass-slaughter of animals the highly deplored battue shooting, which consisted in driving large amounts of birds or hares over the guns, rather than walking up game. As a result Prince Albert soon came to be regarded as unsporting (no doubt the result of his un-English blood!), and his methods of killing animals garnered him the disdain of the nation.

Changing Times

In the second half of the nineteenth century, battue shooting, so much disdained in the 1840s, became the norm thanks to the invention of rapid-firing guns, and the point of the sport was now to shoot as many birds as possible. Careful records were kept on the numbers of prey shot per day – these could amount to a thousand birds or more! Gamekeepers had to provide their master with a satisfying bag, which was not always possible. Moreover, the careful rearing of birds often resulted in birds that were so tame they didn't fly up.

By the 1880s, another important change had taken place: both the opening of the countryside by the railway and finanical problems in rural areas had opened the field of blood-sports for middle class amateur huntsmen, who happily paid for the pleasure of participating in pastimes erstwhile reserved for the landed classes. Country gentlemen might have looked down on these "cockney hunters", but their numbers increased – the country sports were now a truly national pastime.

Amateur sportsmen were made the butt of the joke in contemporary cartoons and literature: they were depicted as shooting at each other, at their host, at the gamekeeper, or indeed, at nothing at all. And if they ever did manage to hit a bird, it must have been by accident or because the bird was unnaturally stupid.

Yet even more severely treated were slick young horsemen, who joined the hunt merely to show off their horseflesh. They are often shown as incredibly rude on the one hand, trampling down other people's gardens or, indeed, other people, or as incredibly stupid and incompetent on the other.

The railway had also opened up Scotland for eager huntsmen, and there shooting was at its most exclusive. With prices as high as £1 per brace and bags of 300, only rich men could afford to shoot grouse (birds were driven after 1870). Even more expensive was deerstalking, which could cost as much as £100 per day.